Liner notes:

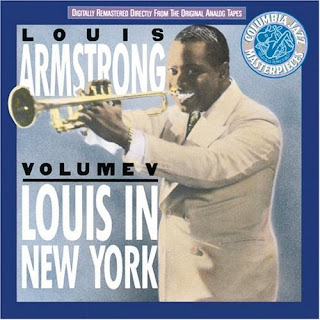

Liner notes:As we reach the fourth volume in this collection of quintessential Louis Armstrong recordings, it is a special privilege to announce the inclusion of two exceedingly rare items. Rare for two reasons; firstly because in the overall Louis Armstrong discography alternative 'takes' of any title were the exception rather than the rule. Secondly, one of these alternative 'takes' has seldom appeared on Armstrong reissues, whilst it is believed the other has not appeared – officially at least – in any other form, being hitherto unissued. More of which later, but thanks are due to Messrs. John R. T. Davies and John Stedman, of JSP records for making them available to us.

The third volume in this set concluded with Knockin' A Jug. With the marvellous music he had created with Jack Teagarden echoing around the Okeh studio on that date, 5th March 1929, Louis Armstrong stayed on for the session which opens this compilation.

Eddie Condon, who largely had been responsible for organising the first session that day – and, rather modestly, had demurred from participating on it – also stayed around to supplement the rhythm section as banjoist on the second.

The rest of the personnel was drawn chiefly from the Louis Russell band, then resident at the Saratoga Club, New York, and soon to make its reputation on record for a swinging, relaxed yet distinctively fiery brand of New Orleans-derived jazz. For this date the Russell band's regular trumpet soloist, Louis Metcalf, and its guitarist Will Johnson dropped out.

The rest of the personnel was drawn chiefly from the Louis Russell band, then resident at the Saratoga Club, New York, and soon to make its reputation on record for a swinging, relaxed yet distinctively fiery brand of New Orleans-derived jazz. For this date the Russell band's regular trumpet soloist, Louis Metcalf, and its guitarist Will Johnson dropped out.In Will Johnson's place came his distinguished namesake Lonnie, (presumably no relation) the influential jazz/blues guitarist. A busy OKeh session musician, Lonnie Johnson already had recorded with Louis Armstrong, supplementing the Hot Five on its final recording date in December 1927, besides working in the studio with the Duke Ellington orchestra, supplying accompaniments to sundry blues singers and making a series of guitar recordings, some as soloist, others in duet with the equally influential Eddie Lang.

I Can't Give You Anything But Love, the hit song from the revue, Blackbirds of 1928 (it is claimed Fats Waller wrote the melody, then in one of his many periods of financial desperation, sold it to Jimmy McHugh for a trifling sum, then Dorothy Fields added a lyric) already had been recorded by several artists, including Louis Armstrong himself, accompanying Lillie Delk Christian in December 1928. This one opens with Louis' muted trumpet delicately reducing the melody to its bare essentials. Then, after J.C. Higginbotham's lyrical solo, the same economical spirit determines the declamatory sometimes dramatic, Armstrong vocal that closely adheres to the written lyric, with just the occasional foray into scat. The ensuing scintillating open horn solo, with some acutely timed breaks, culminates in a thrilling cadenza. Enter the first of our alternative 'takes' which because of its extreme rarity has a somewhat 'low-fi' quality. Yet we may hear enough to realise that such was Armstrong's surety of his ideas, his definitive restyling of a theme, rendered further enhancement or modification unnecessary. The real difference in Armstrong's performance here lies not so much in fresh ideas, but the same ones being given a slightly different emphasis, in phrasing, note values and projection. In other words, "the sound of surprise" as the writer Whitney Balliett once defined the basic essential that determines a worthwhile jazz performance. The cadenza, incidentally, remains identical, although there would be little reason for Louis to alter such a splendid, showcase finale to an altogether remarkable performance.

The strong New Orleans contingent amongst the personnel at the session – Charlie Holmes, Teddy Hill and Eddie Condon were the only non Crescent City musicians, the Panamanian born pianist Louis Russell having settled there in his early 'teens after winning a lottery – perhaps determined the choice of Mahogany Hall Stomp as the second number. In the heyday of Storyville Mahogany Hall had been a luxurious brothel situated on Basin Street – long since demolished then replaced, I believe, by a department store – and managed by Lulu White, the aunt of the number's composer, Spencer Williams. Whatever, the interpretation gives the band greater opportunity to shine than the rather stiff stock arrangement on the previous side, besides highlighting one of Louis Armstrong's most compelling performances. Against the solid foundation of the band, with Pops Foster's four square, slapped bass lines predominant, having announced the piece with crisp phrases, Louis, in commanding form, proceeds to build chorus upon chorus, both open and muted, from some very basic motifs. Variegating them through subtle changes of timing, key and tonal colouring Louis creates a masterpiece of sustained invention. Charlie Holmes, Higgy and Lonnie Johnson each add their distinctive solo voices to heighten the atmosphere.

The strong New Orleans contingent amongst the personnel at the session – Charlie Holmes, Teddy Hill and Eddie Condon were the only non Crescent City musicians, the Panamanian born pianist Louis Russell having settled there in his early 'teens after winning a lottery – perhaps determined the choice of Mahogany Hall Stomp as the second number. In the heyday of Storyville Mahogany Hall had been a luxurious brothel situated on Basin Street – long since demolished then replaced, I believe, by a department store – and managed by Lulu White, the aunt of the number's composer, Spencer Williams. Whatever, the interpretation gives the band greater opportunity to shine than the rather stiff stock arrangement on the previous side, besides highlighting one of Louis Armstrong's most compelling performances. Against the solid foundation of the band, with Pops Foster's four square, slapped bass lines predominant, having announced the piece with crisp phrases, Louis, in commanding form, proceeds to build chorus upon chorus, both open and muted, from some very basic motifs. Variegating them through subtle changes of timing, key and tonal colouring Louis creates a masterpiece of sustained invention. Charlie Holmes, Higgy and Lonnie Johnson each add their distinctive solo voices to heighten the atmosphere.Louis returned to New York, which had taken over Chicago's role as the centre of jazz development, just three months later. His 'timing, as ever, was superb. Fronting the Carroll Dickerson band for some engagements at the famous Harlem night spot Connie's Inn, Louis also became involved in the revue Hot Chocolates. Originally presented at Connie's Inn by the owner, Connie Innermann, the revue transferred to the Hudson Theatre on Broadway, with Louis joining the cast a few weeks after opening night. Accompanied by Leroy Smith's orchestra, his interpretation of Ain't Misbehavin' created a sensation.

The 1928 Savoy Ballroom five recording of Save It, Pretty Mama was a significant departure from his previous recordings, highlighting Louis' mellow, tender treatment of the lyric as much as his trumpet solo, indicating the direction his career would take. Thus the record introduced the concept of Louis as the singing/trumpet playing/entertainer, communicating the strength of his musical personality through a popular song. I Can't Give You Anything But Love reinforced this change of emphasis in Armstrong's role, while Ain't Misbehavin', confirmed it. The spare, sensitive, muted trumpet reworking of the theme in the opening chorus is followed (after Dickerson's gut churning violin passage) by Louis' warmly personal treatment of the lyric, interlarded with easy natural scatting and rhythmic accentuation. The assertive, open horn solo became the definitive trumpet statement of the theme, to which those who performed it ever after would refer – right down to the a capella quote from Rhapsody in Blue including Louis himself. "I believe that great song and the chance I got to play it did a lot to make me better known all over the country," Louis once observed of the number that gave him his first major hit record, besides establishing the song as a standard.

Three days later Louis was back in the studio with the Dickerson band to record a further selection of Andy Razaf/Fats Waller numbers from Hot Chocolates. Black and Blue represented a new departure for both Louis Armstrong and popular song. Hitherto, when, in the rare instances, Tin Pan Alley songs referred to Black Americans, it was as the slow-witted, lazy, contented, eye-rolling, banjo-strumming blackface minstrel caricature. (The blues, largely concerned with the universal human condition, only occasionally alluded to racial prejudice.) Therefore, in trying to convey firsthand experience of the humiliation suffered by Black Americans on grounds of skin colour as an everyday reality, lyricist Andy Razaf broke new ground. (Ironically, Edith Wilson, who introduced the number in the show is best remembered for her role in the Amos 'N' Andy programmes, mercifully long gone.) Gene Anderson's celeste sets the scene, then Louis captures the mood of Fats Waller's plaintive melody in a starkly beautiful solo. The dignified vocal, enhanced by Homer Hobson's discreet obbligato, relates the lyric exactly as written in a spirit of sorrow rather than anger, made even more poignant by the matter-of-fact delivery. Louis' only foray into wordless singing occurs in the modulation between the bridge and the final eight bars: a melancholy cantorial-like lament. Black and Blue is revived today for historic reasons only, apart from the occasional version to be heard performed by some local trad band, when the (Caucasian) trumpet player renders himself ridiculous in both his singing of the lyric and the dreadfully inaccurate Louis impersonation with which he invariably chooses to do so.

In direct contrast, there is a joyful urgency about Louis' interpretation of the up-temp, That Rhythm Man, as he shakes this piece of confection into something more substantial with his innate rhythmic sense. To gauge the timelessness of the Armstrong solo and vocal passages compare them with the accompaniment on Sweet Savannah Sue, which, though within the danceband conventions of the time seem antediluvian.

In direct contrast, there is a joyful urgency about Louis' interpretation of the up-temp, That Rhythm Man, as he shakes this piece of confection into something more substantial with his innate rhythmic sense. To gauge the timelessness of the Armstrong solo and vocal passages compare them with the accompaniment on Sweet Savannah Sue, which, though within the danceband conventions of the time seem antediluvian.Louis' oft-proclaimed enthusiasm for the music of Guy Lombardo has puzzled jazz lovers, for most of whom slow death by drowning in treacle would be preferable to hearing the lugubrious saxophones of the strict tempo dance music associated with him. The ultimate compliment came with Louis' version of Guy Lombardo's Sweethearts On Parade, in which his solo made a glorious conception from an otherwise forgettable tune. That was some fifteen months into the future after the Lombardo influence had first become apparent on the session featuring next items. However, the warbling saxophone section and the strict tempo of When You're Smiling are dispelled by Louis' entry. Over a tight rhythmic cushion, featuring Zutty's deft brushwork, at double the established tempo Louis improvises on the first sixteen bars, creating a superior, more economical melody on the chord sequence. In many respects this anticipates Lester Young's reconstruction of the melody in his solo work on both 'takes' of Billie Holiday's 1937 version of the number. Then, after good solos from Robinson and strong, plus a pedestrian one from Anderson, Louis returns to play the melody straight, but imbuing it with such expressive warmth, and hitherto unsuspected, beauty, it becomes his own creation. The second version contains a personable Armstrong vocal, nicely supported by Hobson, then another equally sublime trumpet solo on the written melody, suggesting it was a set routine. Shelton Brooks' Some Of These Days already firmly associated with Sophie Tucker even then, receives Louis' totally personal treatment. The slighter slower vocal take finds Robinson's trombone solo substituted by Armstrong's jivey evocation of the lyric. The basic pattern of the trumpet solo work is unchanged.

When the show Hot Chocolate finished its Broadway run Louis and the Dickerson hand went their separate ways. Armstrong became featured guest star with the Louis Russell band at the Saratoga Club besides the occasional out-of-town engagement. Fortunately their brief association was documented in the recording studio, the next items on this selection.

Louis Metcalf had left the Russell band since its previous studio date with Louis. In his place was the New Orleans born trumpeter Henry 'Red Allen', who had forged a fiery, defiantly independent style from Louis' influence. It is said on live appearances the Russell Band played its customary book, with Louis taking over Red Allen usual solo spots. This would appear to have been the case on these recordings and it is a tribute to Red Allen's professionalism that he agreed to stay in the trumpet section with lead man Otis Johnson, without trying either to outblow or upstage Louis when the occasional opportunity arose. (Luckily, the prolific Russell band recorded output of the period finds Red Allen giving a wonderful account of his superb style.) Likewise, Louis' total confidence in his playing precluded his relentlessly parading his prowess in Allen's presence. The tenor saxophonist on these sides, incidentally Teddy Hill was eager to make his real contribution to jazz as a bandleader who employed Dizzy Gillespie than as manager of Minton's.

The four sessions combined jazz standards with newer material. From the opening notes of the now seldom played verse to I Ain't Got Nobody, highlighting Foster's bass, there is a poised, exciting sense of swing. After Louis' lovely vocal, Red Allen is glimpsed only briefly in tandem with Armstrong, until the maestro breaks away on a high note, then adds a delightful vocal tag. It is not possible to do justice to either Dallas Blues or St. Louis Blues in the allotted space. The excitement generated on the former by the accord of the band responses to Louis' majestically fervent building of a simple motif is spine tingling. After Higg's lustily elegant treatment of the middle eight of St. Louis Blues, we hear Red Allen's exuberant obbligato to Louis' vocal, a rhythmic reduction of the melody which inspires the rising intensity of the accompanying riff. Higgy returns in a fittingly urgent solo, then picking up on the riff pattern of his singing, Louis creates an electrifying improvisation. This arrangement by the way, was still in the Armstrong book for his 1934 recording of the theme in Paris.

The four sessions combined jazz standards with newer material. From the opening notes of the now seldom played verse to I Ain't Got Nobody, highlighting Foster's bass, there is a poised, exciting sense of swing. After Louis' lovely vocal, Red Allen is glimpsed only briefly in tandem with Armstrong, until the maestro breaks away on a high note, then adds a delightful vocal tag. It is not possible to do justice to either Dallas Blues or St. Louis Blues in the allotted space. The excitement generated on the former by the accord of the band responses to Louis' majestically fervent building of a simple motif is spine tingling. After Higg's lustily elegant treatment of the middle eight of St. Louis Blues, we hear Red Allen's exuberant obbligato to Louis' vocal, a rhythmic reduction of the melody which inspires the rising intensity of the accompanying riff. Higgy returns in a fittingly urgent solo, then picking up on the riff pattern of his singing, Louis creates an electrifying improvisation. This arrangement by the way, was still in the Armstrong book for his 1934 recording of the theme in Paris.The stock arrangement of Rockin' Chair sounds a little stiff, though Louis' dynamic interjections enliven it. Hoagy Carmichael, the number's composer, seems a bit forced at his attempts at comedy as the sedantry geriatric, but Louis adds charm and substance to what would become one of his set pieces (the definitive version behind the duet with Jack Teagarden at the famous New York Town Hall concert). The band loosens up behind the Armstrong solo, with Charlie Holmes' alto saxophone weaving through the sound like a shimmering thread. The other rarity of this set is the 'A' take of this number and probably previously unissued. Despite the slightly poor technical quality, the Russell band's reading of the arrangement is more fulsome; Hoagy sounds more at ease, though still far removed from his customary cool. Again the differences in Louis' playing are in the shifts of emphasis. The familiar '(' take version is perhaps superior but it is nice to be able to have them both for comparison.

The Russell band's valet is responsible for the tasteful brushwork on Song Of The Islands, leaving Paul Barbarin to set the tranquil mood on vibraphone. Louis swings over the rhythm in a reflective, muted solo. The gentle thrust of Louis' scatting, over the other stodgy vocal tones of other band members pretending to be Hawaiians curiously is moving. The open horn solo taps a new vein meditative beauty in Armstrong's playing on an otherwise merely pleasant tune.

Blue Turning Grey Over You, another Fats Waller/Andy Razaf evergreen, is, apart from a leisurely Higgy solo, Louis all the way. This muted work and singing both wistfully enhance the reflective mood. An early forward looking example of intimate jazz balladry.

To close we hear pianist Buck Washington, after a little 'coaxing' from Louis set the scene for Dear Old Southland, a seldom heard number number from Henry Creamer and Turner Layton, the composers of After You've Gone among many other standards. Mindful perhaps of the number's origins in the spiritual Deep river, Louis mood is one of rhapsodic splendour, then as the tempo slightly increases to a stately tango the lower notes resonate with a solemn reverence that is neither pompous nor funereal. The sudden change of pace lightens Louis' mood for a deftly swinging chorus before the majestic cadenza. A wonderful example of Armstrong's virtuosity and emotional range.

To close we hear pianist Buck Washington, after a little 'coaxing' from Louis set the scene for Dear Old Southland, a seldom heard number number from Henry Creamer and Turner Layton, the composers of After You've Gone among many other standards. Mindful perhaps of the number's origins in the spiritual Deep river, Louis mood is one of rhapsodic splendour, then as the tempo slightly increases to a stately tango the lower notes resonate with a solemn reverence that is neither pompous nor funereal. The sudden change of pace lightens Louis' mood for a deftly swinging chorus before the majestic cadenza. A wonderful example of Armstrong's virtuosity and emotional range.This compilation represents just over one hour in Louis Armstrong's eventful, lengthy career, in which he creates music of beauty, depth, richness, power, imagination and profound conviction.

- Sally-Ann Worsfold.

------------------------

Tracks:

Louis Armstrong and his Savoy Ballroom Five

01 I Can't Give You Anything But Love 3:26

02 Mahogany Hall Stomp 3:18

Louis Armstrong and his Orchestra

03 Ain't Misbehavin' 3:16

04 (What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue? 3:03

05 That Rhythm Man 3:05

06 Sweet Savannah Sue 3:09

07 Some of These Days [Instrumental] 2:55

08 Some of These Days 3:07

09 When You're Smiling [Instrumental] 2:53

10 When You're Smiling 3:25

11 After You're Gone 3:17

12 I Ain't Got Nobody 2:41

13 Dallas Blues 3:11

14 St. Louis Blues 2:58

15 Rockin' Chair (with Hoagy Carmichael) 3:17

16 Song of the Islands 3:32

17 Bessie Couldn't Help It 3:24

18 Blue, Turning Grey Over You 3:31

19 Dear Old Southland 3:21

20 Rockin' Chair 3:16

Louis Armstrong and his Savoy Ballroom Five

21 I Can't Give You Anything But Love 3:27

Recorded from March 1929 to April 1930

Please, email for the link:

romanil2010@yahoo.es

..................................

No comments:

Post a Comment